Relics of a Bygone Era

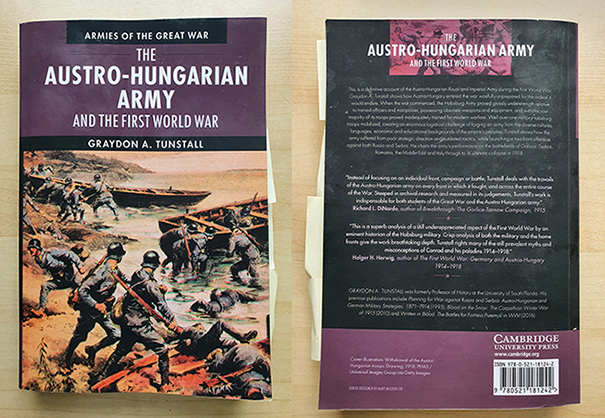

The Austro-Hungarian Army and the First World War, by Graydon A. Tunstall, published by Cambridge University Press, 2021, 466 pages, £26.99, reviewed by Tom Isitt

Schlamperei is a word used by the German army during the First World War to describe the Austro-Hungarian military. It means slack, confused, lazy and inefficient. It’s also the perfect word to describe “The Austro-Hungarian Army and the First World War”, a book by Graydon A. Tunstall, a former professor of history at the University of South Florida.

It’s not often that a venerable publishing institution such as Cambridge University Press puts out a book that is riddled with errors, but with this book CUP has managed to do exactly that, and has published possibly one of the worst military history books ever written (and there’s some strong competition out there).

“The Austro-Hungarian Army and the First World War” is the latest instalment in CUP’s Armies of The Great War series. Other books in this series have been well reviewed, and are highly regarded within the WW1 history community. Tunstall’s book, however, falls a very long way short of what we have come to expect. Embarrassingly short.

Described by CUP as “a definitive account of the Austro-Hungarian Royal and Imperial Army during the First World War”, this book is confusing, repetitive, has unreadable maps, and contains dozens of errors and spelling mistakes. The author’s English is confused, his grammar is bad, and his sentence construction is often incomprehensible. None of which will come as a surprise to anyone who has read his frankly baffling book about the Carpathian campaign.

It’s bad enough that CUP has accepted a very poor manuscript, and failed to edit it properly, but it then persuaded two eminent historians to endorse it. “Steeped in archival research and measured in its judgments, Tunstall's work is indispensable for both students of the Great War and the Austro-Hungarian army,” writes Richard L. DiNardo, author of “Breakthrough: The Gorlice-Tarnow Campaign, 1915”.

“This is a superb analysis of a still underappreciated aspect of the First World War by an eminent historian of the Habsburg military. Crisp analysis of both the military and the home fronts give the work breathtaking depth. Tunstall rights many of the still prevalent myths and misconceptions of Conrad and his paladins 1914-1918,” says Holger H. Herwig, author of “The First World War: Germany and Austria-Hungary 1914-1918”.

Which makes one wonder, did Herwig or DiNardo actually read this book? If they did, and these are genuine opinions, then what does that say about their own standards of writing and research? And if they didn’t actually read this book, what does that say about their academic integrity?

I emailed Herwig and DiNardo to ask them about this. Neither has replied. But these two historians have form when it comes to this kind of thing. They also wrote glowing testimonials for Tunstall’s awful book about the Carpathian campaign.

To give you a few examples of how wide of the mark DiNardo and Herwig are, here’s an example of Tunstall’s abject confusion from page 323 of the paperback edition: “the Italian Army had been soundly defeated at the battle of Caporetto, although it continued to contest Habsburg forces in the Slavic areas of Croatia, Slovenia, Dalmatia and Istria.” The Italian army never fought in Croatia, Dalmatia or Istria, and didn’t fight in Slovenia after Caporetto. This is such a colossal, inexplicable error that you wonder what’s going on in Tunstall’s head. He has invented an entire WW1 military campaign that never existed.

Concerning the Brusilov Offensive on the Eastern Front, Tunstall says “Russia regained all the territory it had surrendered during the 1915 Gorlice Tarnów offensive, and again deployed troops on the Carpathian Mountain foothills.” This is complete nonsense. The Gorlice-Tarnów offensive by German forces saw a 400km retreat by the Russian army. The Brusilov Offensive recaptured a tiny percentage of what was lost, advancing barely 80km in the southern sector of the Front. Tunstall is getting the really basic stuff completely wrong. If he gets this kind of thing wrong, what about the small stuff?

Well, here’s an example from a chapter about the Italian front: “Called the three saints, Mt. Sabatino was north of the city, Mt. San Michele to the south and Mt. San Gabriel to the west.” Twenty four words, four mistakes. Sabotino is spelled incorrectly (throughout the book), Sabotino was not one of the Tre Santi (Monte San Daniele was the third), San Gabriele is spelled incorrectly (throughout the whole book), and San Gabriele is NNE of Gorizia, not west. Clearly Tunstall didn’t bother himself with looking at a map. And the readers will be none the wiser because the maps in this book are mostly unreadable:

I don’t know how many more examples there are like this, because my “expertise” is the Italian Front, but I counted more than 70 basic errors and misspellings of place names in the small sections about Italy (around 25% of the book). In these, Tunstall gets his geography confused, his place names misspelled, and his battles mixed up. Not ideal in a military history book.

But worse, much worse, is the passage that reads very like one from John Gooch’s “The Italian Army and the First World War” . This is one of Tunstall’s paragraphs on page 304, about the Italian Front in 1917:

“During early summer 1917 Italian lines extended above the Asiago Plateau and basically ran north-south from the Brenta to the Assa Valley facing Austrian positions entrenched along the line of some two-thousand-meter high mountains. The Eleventh Isonzo offensive was designed to achieve a favorable position to attack the Val Sugana Valley after the Austrian counter attack was launched on Mt. Hermada between June 4 and 10 during appalling weather. The effort was immediately repulsed except on the northern flank of XX Corps, where it terminated the next day because of the inclement weather conditions.”

And this is from page 222 of John Gooch’s excellent “The Italian Army and the First World War”, published seven years ago:

“In the early summer of 1917, the Italian lines above the Asiago altopiano ran more or less north-south from the Brenta valley to the Assa valley, facing Austrian positions entrenched along a line of mountains some 2,000 metres high...The offensive, designed to put the Italians in a favourable position to attack the Val Sugana, was brought forward after an Austrian counter attack on Monte Hermada between 4 and 6 June...The [Ortigara] attack, launched at 0515 on 10 June 1917 in appalling weather, was immediately repulsed everywhere except on the northern flank of XX Corps.”

As it stands in Tunstall’s book, this paragraph makes absolutely no sense at all. The Eleventh Isonzo was not designed to achieve a favourable position to attack the Val Sugana, it was designed to break through Austrian positions of the Carso 100 miles to the east. The Austrian counter-attack at Hermada was on June 4, and took place in warm, dry weather. And in June 1917 XX Corps were at Ortigara, not on the Isonzo, 100 miles distant. Tunstall has somehow confused Monte Ortigara with Monte Hermada (102 miles apart), and confused the Battle of Ortigara with the Eleventh Battle of the Isonzo (two months and 100 miles apart).

This paragraph encapsulates everything that is wrong with this book. Tunstall and CUP have shown their ignorance, their laziness, their schlamperei. That this paragraph exists in a book claiming to be a definitive work on the subject is shameful.

Like the Austro-Hungarian empire in 1918, Tunstall seems to be a relic of a bygone era. He got his history degree in 1963, his MA in 1970, and his Ph.D in 1974. He has spent the last 27 years working in university administration, and seems out of touch with current research (there are several recent books on Austria-Hungary and the Eastern Front which are absent from Tunstall’s bibliography). This book was supposed to have been published in 2014, but for some reason it didn’t appear until 2021 and it feels like the second half is a hasty conclusion to a stalled project.

When asked about the huge number of mistakes in this book, Cambridge University Press had this to say:

“As a responsible publisher, we strive to produce work of the highest possible quality and take all such issues seriously. This book went through a rigorous editorial process prior to publication, including peer review by leading experts in the field.

“Following your email, our editorial team is working with the author to review the text and to correct any errors, including the misattributed reference you identified. We have found no evidence of plagiarism.

“Once the review is complete, the electronic version of the book will be updated, with any corrections clearly signposted. Physical copies are printed for individual customers on demand, meaning that any corrections will immediately flow into future printed versions.”

It was pointed out that it was dishonest to continue selling the book knowing that it was not fit for purpose, and they informed me it would be withdrawn for sale. So far that has not happened, although they have refunded me the cost of the book.

The claim that the book went through a rigorous editorial process is soundly contradicted by the dozens of errors contained therein, and whoever peer-reviewed it was clearly not an expert in their field because they failed to spot three very significant mistakes. This sorry episode reflects very badly on the author and the CUP, and calls into question the integrity of those who fulsomely endorsed this steaming pile of schlamperei.